Written by Karina Barquet and Ylva Rylander, Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI), and Mats Eriksson, Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI).

The profound impacts of global warming on ocean temperature and acidity, and of the accelerated melting of the cryosphere on sea-level rise, are increasingly evident. Sea-level rise will enhance storm water surges, coastal erosion, and saltwater intrusion and thus threaten coastal communities and areas important for food production, such as large deltas. The territorial consequences of sea-level rise could jeopardize international cooperation, leading to tension and conflicts. At the same time, changes in ocean temperatures are threatening marine ecosystems and food security.

On 6 November 2020, the Stockholm Climate Security Hub, represented by the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI), Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI), and Stockholm Resilience Centre (SRC), organized a science-policy workshop for invited experts and agents of change on the links between climate change, ocean, and security.

In cooperation with the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management (SWAM) and the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Sweden (MFA), the workshop brought together key scientists and decision makers from northern Europe to present the latest research on the topic and to discuss how science-based policy could help to address global ocean-related security challenges driven by climate change. The workshop was chaired by Karina Barquet (SEI) and Mats Eriksson (SIWI).

The security impacts from climate change with the ocean as a driver follow two main pathways:

- Consequences from sea-level rise on coastal landscapes and communities; and

- Consequences from sea-level rise and warmer temperatures on marine territorial delimitations and resource security.

The first speaker, Jochen Hinkel, Head of Adaptation and Social Learning at the Global Climate Forum and one of the authors of IPCC’s Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, explained that “we can surely expect that much suffering in society will take place during this century, and this suffering will be uneven.” In fact, it can already be seen that rich urban centres have coastal defences, while poor rural coastal areas increasingly experience human security challenges as livelihoods are affected. This may be a matter of state and collective security.

Beatrice Mosello, Senior Project Manager at Adelphi, highlighted Bangladesh as an example: “Bangladesh is a country experiencing all possible types of vulnerabilities apart from climate change, including political risks, refugee camps, rapid urbanization, and high rates of poverty and inequality. Here, climate-driven insecurities upon the ocean and coasts stem from loss of land and livelihood from sea level rise. A one-meter increase will cause saline intrusion in half of Bangladesh and inevitably lead to massive displacement of people, which could spiral local, national and regional security risks.”

Rising sea levels also have other security implications. As the rising sea encroaches on physical coastlines, it potentially impacts on legal baselines. The location of borders at sea are defined by the coastline, so inundating the coast will lead to loss of land territory as well as shifting maritime limits inland, and impacting the extent of, for example, Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ).

Clive Schofield, Head of Research at the World Maritime University-Sasakawa Global Ocean Institute, said: “Countries have the exclusive right to manage and use all natural resources within their EEZ, including fish, minerals, oil, and natural gas. EEZ cover about 39 per cent of the ocean’s surface and account for more than 95 per cent of global marine fish catch. So, you could say they are pretty important.”

As if sea-level rise were not worrisome enough, half of the world’s 512 potential maritime boundaries have not yet been defined. This means that the combination of sea-level rise with unsolved jurisdictions is potentially explosive and deserves attention.

Global warming also has a direct impact on the ocean, leading to higher water temperatures and changes in pH levels. This in turn will have profound impacts on marine ecosystems and food webs. Professor Anna Gårdmark of the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences showed that, due to warmer oceans, sea water acidity has increased by over 25 per cent since preindustrial times. Warmer and more acidic seas are in turn altering food webs by causing shifts in population structures that favour smaller individuals, putting populations of the larger predators at risk of collapse.

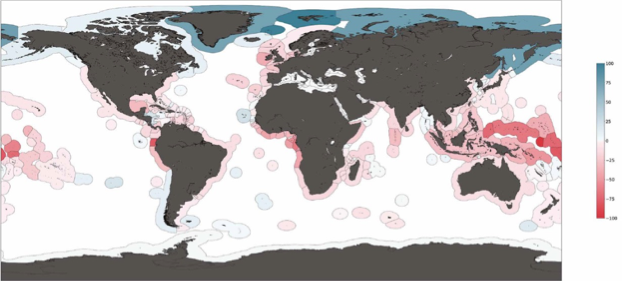

The alteration of food webs is causing an overall reduction in global fishery production, but regional changes can also be observed, as illustrated in Figure 1. Here, red areas will experience decreases in primary fish production, whilst blue areas will experience increases. The red areas coincide with the world’s most populated areas, which also have large forecasted population increases.

Figure 1. Percentage of change in maximum catch potential until 2050 under global warming (RCP8.5). Anna Gårdmark, ‘Climate, ocean and security: Response to ocean-driven security challenges’, 6 November 2020.

“Warmer oceans are already impacting global fish markets and local fish industries, which millions of people globally depend on for survival,” explained Gårdmark.

What are the options for dealing with these challenges?

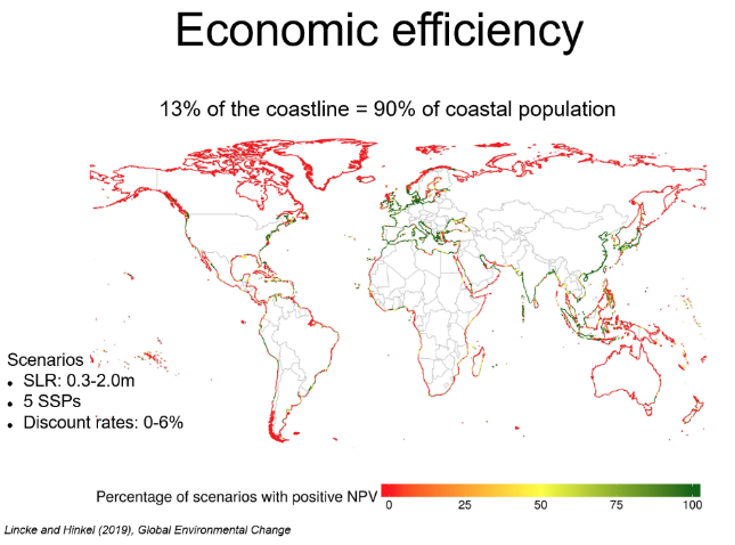

“Mitigation and adaptation will not stop climate change but can dampen its impacts.But mitigating and adapting will cost money, which means it is important to assess where interventions might be most effective,” said Hinkel.

Mitigation and adaptation efforts would be most effective on 13 per cent of the world’s coasts. These areas are inhabited by 90 per cent of the global coastal population, according to a study by Hinkel and colleagues. But can we afford this? And, more importantly, who can afford to mitigate or adapt?

Figure 2. Coastal areas where mitigation and adaptation measures could be more cost-efficient in terms of net present value (NPV, in green). Figure courtesy of Jochen Hinkel. (SLR= Sea-Level Rise; SSP=Shared Socioeconomic Pathways).

Hinkel warns that ensuring climate change security will increasingly be a matter of wealth. With a projected sea-level rise of 0.4–2m during the 21st century, we can expect the world to become even more divided.

Cooperation and policy actions

It is clear that international and regional cooperation will be important in addressing anticipated scenarios. One important global cooperation mechanism is the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), which will turn 40 years old in 2021. CCAMLR is an international commission with 26 members, and a further 10 countries have acceded to the Convention.

“The sudden ocean changes and the Antarctic ice sheet play a very important role in the global ecosystem,” explains Jakob Granit, Director General at SWAM and the new chair of CCAMLR. “Over past years, we have seen significant events, including 20 degrees Celsius in Antarctica and large calving of icebergs. These events are happening much more rapidly than we previously have seen.”

“To improve our understanding of the impact’s climate change will have on the ocean globally, it’s crucial to continue carrying out research in cooperation with all member countries. CCAMLR has and will continue to be an important vehicle for this,” said Granit.

Her Excellency Helen Ågren, Ambassador for the Ocean, Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs, emphasised that international cooperation is a key feature of Sweden’s official stance towards ocean governance. By incorporating conflict prevention, gender, and social equity into broader discussions on ocean sustainability and adaptation to climate change, Sweden intends to raise the level of ambition in international cooperation.

“When we talk about climate, the ocean and security, we need research on investment needs for adaptation, but also aligning global work to national policies and measures. We need to take into consideration consumption and production patterns when we think about ocean sustainability and the blue economy and ensure coordination within ministries and governments as well as with local communities,” concluded Ågren.

The official report of the Climate, ocean, and security science-policy dialogue can be found here.

The Stockholm Climate Security Hub is an initiative of the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs that builds on cooperation between the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI), Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI), and Stockholm Resilience Centre at Stockholm University (SRC).